EXCLUSIVE: Filmmaker Nora Jacobson Discusses ‘Delivered Vacant’, the Award-Winning Documentary on Gentrification in Hoboken

Mile Square Theatre‘s playwright-in-residence Joseph Gallo recently interviewed Delivered Vacant (1992) filmmaker Nora Jacobson in her editing studio in Norwich, Vermont as part of his research for the stage adaptation of his documentary play Yuppies Invade My House at Dinnertime, detailing the arson fires and gentrification of Hoboken in the late 1970s and 80s.

Called “an urban epic” by The New York Times, Jacobson’s film has long been heralded as the definitive document of that era, its aftermath, and the often unseen impacts of gentrification.

**********************************************

Nora Jacobson: I was working in a loft building on… right on the southern edge of town, and I think it’s still a factory building with artists still living there. Do you know what I’m talking about? Do you know what building it is?

Joseph Gallo: The Neumann Leathers Building.

N: The Neumann Leathers Building. Yeah… that’s where Delivered Vacant was edited. I had my editing room there. The last couple of years when I was finishing Delivered Vacant, after I got burned out, I finally found an apartment after floating around for a bit… I got an apartment on Bloomfield… 422 Bloomfield.

J: Why did you move to Hoboken?

N: I moved to Hoboken because I had worked on a documentary film right out of college. I gotten a job with a documentary filmmaker from New Hampshire and he was working on a film for the National Trust for Preservation. And we were traveling around the country documenting adaptive reuse.

That was the term they used back in those days. They would reuse a building. This was in the 70s. The mid-70s, I guess. And they would take a building and reuse it turn it into an apartment building or a different kind of building. And he somehow heard about Hoboken and the Section 8 housing that was in the Clock Towers and so we went to Hoboken and did a whole episode on the Clock Towers (A Sense of Place). The Clock Tower project in Hoboken – Michael Coleman was the developer at that time. And I knew about Hoboken.

Neumann Leathers Building

And then when I went to Chicago to go back to grad school and I wanted to move back East after that in 1980. Some friends of mine had gotten kicked out of their loft on the Bowery in New York City, and they had moved to a loft building on Third and Adams. And that building is of course now condos. But then it was an old factory building. My friends were from Dartmouth, but they were artist types you know like writers and musicians. They had gotten a loft there. Very crude. Very simple. And they needed a roommate. And when I wanted to leave Chicago they said, “Why don’t you come to Hoboken? We just got kicked out of our loft on the Bowery.” And I knew Hoboken, because I had worked on that film. And I said, “Hoboken! I remember Hoboken!” And so I moved into that loft in 1980, I guess.

And then I spent the next couple of years, because I had an MFA, becoming a teacher of film at Ramapo College in New Jersey. The New School. Princeton. And I was also trying to make a living as a filmmaker. In fact, I did projections for Ping Chong. He had a job at the time showing movies to Wall Street people at noon. I was doing a lot of different things—house cleaning, making these short films—I moved out of the loft. I was there for a couple of years, and then I found a rent-controlled apartment on the second floor above Dom’s Bakery.

J: It’s still there.

N: And one of the little projects I gave myself to learn how to be a filmmaker, because I didn’t think I learned in grad school, was to make a little film, a little documentary about Dom’s Bakery. I would go down and film at night…and I added the sound…

J: Does the film still exist?

N: That film? Yeah, yeah…it’s part of a series that I call Hoboken Home Views—sort of the precursor to Delivered Vacant.

Dom’s Bakery – 506 Grand Street, Hoboken

J: So you made these shorter pieces to teach yourself how to be a filmmaker?

N: Yeah.

J: At which point do you make the transition from those films to realizing that there’s something bigger going on?

N: Well…I started filming at Sister Norberta’s shelter on Third and Adams…I started volunteering there. Now this is when I first moved there, and I was depressed, and I couldn’t get a job as a filmmaker.

J: The young artist’s blues.

N: Yeah… right? I was like, “What am I doing?” And then I thought if I do something for some other people maybe I’ll start to feel good about myself. And I did. And I wanted to make a little film about the shelter. But I realized pretty quickly that there was something more going on. That homelessness was one facet of something larger.

There was this film called Shoah by Claude Lanzmann, which I greatly admire. It’s about the Holocaust but from a very interesting point of view. Like it doesn’t show any archival footage of emaciated people coming out of concentration camps. He only interviews survivors, bystanders, and perpetrators, and he just sits and talks with them. And it’s an amazing film because it’s all these interviews. Talking heads. When you think of talking heads it’s sort of a disparaging remark. But in this film, the talking heads are so incredible that you just hang on to every word—even though they are in German most of them and so you’re reading subtitles. But just looking in these peoples’ faces…it’s really about the whole mechanism of the Holocaust like everything about it…what went into planning it…what went into creating, implementing it…and so I decided in my naivety as a young artist and filmmaker that I wanted to make a film about gentrification that had the same depth. And so that’s what I did.

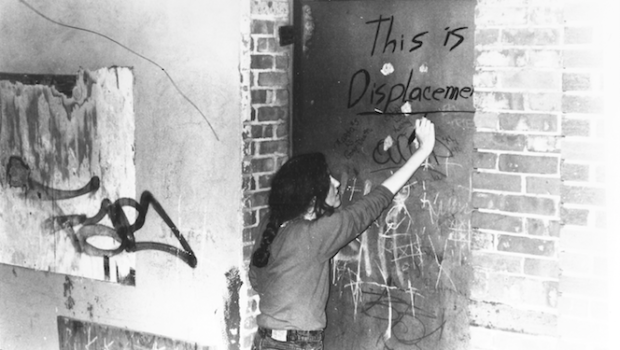

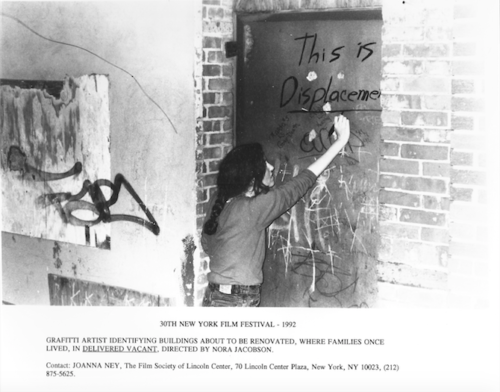

Buildings at 10th & Willow (image via Nora Jacobson)

I bought a 16mm camera that could record sync sound, because all the other films I had up to that point were shot with a Bolex, a 16mm wind-up with a separate little reel-to-reel tape recorder that I would carry around. I would shoot and then I would go and record sound and I would put them together. But buying a 16mm sync sound camera allowed me to shoot sync sound interviews. And it also meant that I needed to have a sound person. I tried a couple of times, but I remember going to a City Council meeting with my tape recorder and my camera and I would forget to take it off pause, and it was a disaster…and not having the right microphone. And so I stared working with a sound person, and the first one I had was a young woman named Deb Augsburger who had moved to town and you know she was sort of eager, and she was actually a tenants activist so she worked part-time for me whenever I needed it I would call her and she would come and hold the boom.

I had a number of other sound people that were all in Hoboken, and it was an amazing time because these were all people who lived on the margins who could work you know because they didn’t have real jobs. And whenever I would say, “Could you meet me tomorrow morning or this afternoon?” They could. And we shoot for two hours and I would pay them $10 an hour. And that’s how I was able to make Delivered Vacant. I wouldn’t have been able to make it if I had continued with a wind-up Bolex. It moved my filmmaking up to a new level.

J: It sounds like you learned on-the-job.

N: I wasn’t schooled in the conventional way that you make documentary films. I came at it from a completely different background.

First-of-all, nobody told me I had to identify anyone in the film. I don’t use music, either, you know, I only use music within the context of the filming. That really comes out of my unconventional filmmaking background. In those days working 16mm I would have had to do all that in post-production. Someone would have had to create all those titles for me. I don’t think it even occurred to me. Of course, at the end I list everyone.

J: When you were making this film, and you see a guy like Eddie (a retiree, interviewed in the film), who seems like a good guy, but then you look at the building he lived in, weren’t the developers making something live-able out of something that was un-live-able?

N: I disagree. I don’t think it was un-live-able. And for those buildings that were already empty, “How did they get to be in such a state of terrible disrepair?” Remember that a lot of these landlords would let their buildings fall into disrepair while tenants were still living there. And that was their big justification. That Hoboken was a wreck and that they saved Hoboken by coming in and fixing up these wrecked buildings.

image via Nora Jacobson

J: Some of the buildings I heard were simply abandoned. Some landlords just gave up. Some landlords bought out their tenants, some buildings were allowed to fall into disarray, and there were people being burned out…although no one was ever convicted of arson. And what’s crucial to telling Hoboken’s story is where you decide to pick up the tale.

N: Right.

J: That’s crucial. How did Hoboken get this way? That’s the important question.

N: The story about the tenants on 11th and Willow, which we see later (in the film) they talk about the fact the landlord won’t fix up the building. The building fell more and more into disrepair.

J: The economic history of Hoboken…let’s look back to the advent of containerization on the piers, and that industry dies. And the factories. The facilities are no longer up to standard and they move to the suburbs. And there’s no industry left in Hoboken. There was no work for anyone. Where are the workers going to go?

N: That was a gradual process.

J: Over 50 years.

N: But when I first moved to Hoboken there were still factories in the back of town.

J: And Maxwell House.

N: It’s a complicated process that isn’t just about evil landlords trying to evict tenants. It’s about automation. It’s about the nature of labor. The work. The industry. We have this one developer say, “We buy buildings in a terrible state of decay and remove everything.” The everything being the tenants as well. And start over again.

J: What did you think of the labeling of the city as having a renaissance?

N: Oh…I was always…aware of the irony of calling it a renaissance, because my feeling about it was that Hoboken was already great and that it didn’t need to have a renaissance, especially that kind of renaissance. I was always cynical about that label.

That’s why I titled the film Delivered Vacant, because that was a real estate term used when people were trying to sell a building. But I knew what that meant…it meant it was great for the developer, but it’s terrible for the people who were living there. They somehow had to be gotten ridden of before the building was delivered.

You can’t say that you care about people and then still cash in. If you have people living there? I don’t know about that that decision. It’s problematic.

I would never want to be a landlord, because I would never want to be in that situation. The whole business of real estate, whether you are a developer or landlord is one big compromise. I would never want to be in that situation of wanting to cash in on a building when I knew that there were poor people living there and you know they are going to have a hard time finding somewhere to live.

Steve Cappiello – Mayor, City of Hoboken, 1973-1985 (center) – surveys a fire at 67 Park Ave in October 1981 (via Facebook – Hoboken Fire Department Memories)

J: What did you think of the mayor at that time—Steve Cappiello?

N: I liked Steve. He was a charismatic guy. But… he wanted to change Hoboken…him and people like him.

He espoused that whole philosophy that we need to clean Hoboken up. We need to make it nice. And we’ll profit from it… so…

But I still liked him as a person—he was always charming to me. But I’m aware of that need to separate yourself from liking a person and your awareness of what they do.

He says (at one point in the film) that he “wants people to have a better quality of life.” And I’m very interested in how people use language, because what he’s saying there is that he’s not talking about the people who already live there, he’s not talking about giving them a better life. He’s colliding two ideas. He’s saying that people are getting a better quality of life—but the people who are going to buy condos, they already have a good quality of life. He (Cappiello) was a great salesman.

I heard that he wanted to sue me for defamation. I don’t know what he could have sued me for. But that’s what I heard. Even though he was still friendly with me, after the film came out he was angry at how he was portrayed.

Tom Vezzetti, Mayor of Hoboken from 1985-1988 (image via Hoboken Historical Museum)

J: What did you think of Tom Vezzetti (who defeated Cappiello for mayor in 1985)?

N: I was like everyone else—amazed by him, amused, a little skeptical of him.

He used to say that line, “Your good looks are exceeded only by your charming personality.” I was always embarrassed when he would say that, but then when I would see how people would respond. They were charmed. They would laugh. People liked it.

I think a lot of people were skeptical of him, but he allied himself with the reformers, newcomers. And they embraced him. He represented the idea of “Do you want to live in Hoboken?”

He didn’t treat me any different than anyone else. He would always greet me. I didn’t know if he knew my name or not but I interviewed him, filmed him a lot. He loved being filmed.

When he died I was deeply distressed. I had never seen an open casket before his funeral. But I remember filming. I thought it was important to film his funeral, even though some council members were mad at me. You can see them throw me these mean looks when I was filming the procession. And I got other people to film from the roof of other buildings. I just felt it was a very important moment and then after the procession (from City Hall), I put down my camera and I went to the funeral home, and it was an open casket and I looked in and there he was, and I burst into tears uncontrollably. It was the first time that had ever happened to me. To burst into tears without any warning. I didn’t think he was so important to me. That was a bizarre thing to have happened.

The best thing about Vezzetti and the reformers was they embraced the question of, “How do you have change, which can be a good thing, without hurting people who are powerless?”

Can you have change, and still keep people in Hoboken? That became what the film was about—how these administrations tried to bring in new ideas and yet curtail displacement. How do you protect people and still have change?

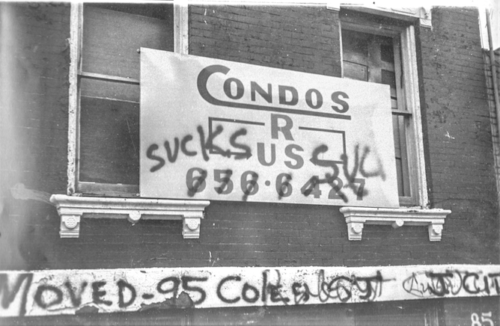

Real Estate sign defaced (Sheilah Scully photo)

J: What did the developers think of you?

N: I think some developers saw me as an ally. I was a newcomer, but I was an artist who was doing this interesting project about Hoboken. Danny Gans and George Vallone donated money to the film. They’re an example of developers who were committed to Hoboken. They’re still in Hoboken. They were sympathetic. Enlightened.

Some developers… hated me. For them it was all a quick profit—you buy up a block, you get rid of the tenants, you rehab it and sell it and then you’re gone.

J: When you watch the film now do you have a vivid memory of making it?

N: I do. Sure. I remember there being awkwardness in the beginning, but I became a fixture around town. Those first City Council meetings I was nervous, but by the end I would go wherever I had to go to get a good shot.

J: When did you start shooting?

N: I started shooting in 1984… maybe sooner.

J: What year did the film come out?

N: September 1992.

J: Where did you first screen the completed film?

N: It was at the New York Film Festival.

J: Do you remember what that was like?

N: Oh, yeah…very, very well. For a couple of reasons. One, during the screening, the guy who had given me the money to finish the film, John Pierson, who was an Indy producer…

J: …had you shown him a rough cut?

N: Yeah. I had been to the IFP to try to raise financing. And I knew that he was an indy fundraising superstar at the time. And I was going down the escalator at the Angelika in New York where it took place, and I saw him going up and when I got to the bottom I rushed back up again, and I said, “Hey, I would love to tell you about my film.” He had just done Roger & Me and I knew he had finishing funds. So to my surprise he was very personable, and he said, “Oh, yeah…bring me a sample…show me some footage.” And I did a couple of weeks later, and he loved it.

At the time the film was over three hours, and he said, “If you can cut it down to two hours, I will give you the money to finish it…” His money came from Island Pictures at the time. And he came to my editing room, and he got it in front of the people at the Toronto Film Festival and they didn’t want it and at that point he basically disappeared. He had committed to giving me the money and I had hired a sound editor and put everything into place to finish it and he suddenly stopped taking my phone calls.

And I was beside myself…“How was I going to finish this film?”

I remember writing him a letter basically shaming him, saying, “Look, you promised me…and I know not getting into the Toronto Film Festival was hard, but…you promised.” And the following week I got a call from the New York Festival saying that they wanted it…he (Pierson) submitted it…and he immediately gave me the money to finish.

View of Hoboken’s proximity to NYC (image via Nora Jacobson)

J: What was the screening like?

N: I remember he was sitting in the back with Michael Moore watching the film. And I could tell that Michael Moore didn’t like it very much. And, afterwards, John told me that Michael said, “It’s not commercial.”

J: That was Michael Moore’s take on it?

N: Yeah.

J: That’s funny because the Village Voice reviewed the film, and said, pointedly, “Has the charm but none of the smartass posturing of Roger & Me.”

N: Yeah…yeah…yeah…and John…he had given me the money already and he thought he would cash in on the film the same as he had done with Roger & Me, but that didn’t happen. Because of the length, because of the type of film it was…anyway…but that was minor.

It didn’t bother me. It was a great big success, and there were tons of people there, and people were responding to the film during it…and then we showed it at the Elks Club in Hoboken, and I know that Cappiello was there. And that’s when I heard afterwards that he was thinking of suing me.

J: What does John Pierson think of the film now after the fact?

N: It’s in his book Spike, Mike, Slackers, & Dykes. He says it’s one of his favorite films.

J: So he rose above it not being a commercial venture, but he could see it’s worth as an artistic venture.

N: Yes.

J: After how many years of working on it what did you feel when it was done? Were you depressed?

N: Not at all.

Luxury Condos – Sheila Scully photo

J: What was the highlight? What was the perfect moment from that night at the New York Film Festival?

N: I guess it would be having my community there.

J: And no bad reviews.

N: And my parents were there, too. And my father who was an old theatre guy knew that the reviews would come out that night at midnight and they were staying in a hotel by Lincoln Center where the film was screened. And he got a copy of the New York Times when it first came out and he was ecstatic. In fact, that might be the high point, my father being so happy about the success of the film.

J: That’s beautiful.

N: Yeah. (She chokes up here, a pause.)

J: What about Sundance?

N: Sundance was a difficult experience for me. Understand that this was me coming into an arena I had never been to before. Success—this kind of success. This was the first time I had ever had any kind of success on this level. And it’s unknown until it happens.

I went to Sundance alone, and what I learned was you never go to a festival alone. You bring your posse.

John Pierson, he was the one who got it in front of John Gilmore at Sundance and he accepted it —this was right after the New York Film Festival. But back in 1993 Sundance wasn’t yet the crazy madhouse that it was today. I’m not sure Delivered Vacant would be accepted at Sundance today.

My friends were excited for me—they helped me buy clothes, and I was put up in a condo in one of the mountain villages nearby.

When you’re accepted to Sundance, your main job is to get people to see your film—to get an audience, to get people to write about your film. It’s all about marketing.

If you go there alone you, already feel vulnerable because your work is out there and then you’re supposed to get distributors in to see it. I remember the first screening and John wasn’t around because he was the rep for another film as well, and he thought that film was more commercial. So I was alone in this theatre—and I remember feeling so alone.

‘Delivered Vacant’ promotional information from the 1992 New York Film Festival (image via Nora Jacobson)

J: Was the theatre filled?

N: No. It wasn’t full, but there was a sizable number of people, and towards the middle of the screening I started to hear these sounds outside, and it was all the people gathering for the next movie, and it was very noisy, and distracting for us watching the movie in the theatre.

I remember when the film was done, I overheard this young woman in the row in front of me say, “That was the most boring movie I have ever seen.” I basically felt pretty terrible.

Now even though my film was at Sundance, and that in itself was a success, I felt like a failure—so that wasn’t fun.

I mean, I did have people who loved the film, who became champions of it—like Ron Yerxa who produced Election and Little Miss Sunshine. And I met other people too, who wanted to see more work of mine. So I did learn a lesson from that—don’t go alone to film festivals.

J: But didn’t it then go on to win the “Golden Gate Award” at the San Francisco International Film Festival?

N: Yeah. That was fun. A lot of friends who lived in the Bay Area came, and it did go on to play in New York at the Cinema Village downtown. But even now, when I watch the film, I can see why it wasn’t a big commercial success.

J: Did this limit you at all going forward?

N: No. Not at all. I immediately jumped into my first narrative feature.

J: Did you find it was easier to get funding?

N: Because of Delivered Vacant, yes. Sundance and the New York Film Festival are the pinnacle of indy film to this day, and to have that be your first experience…it was amazing.

Delivered Vacant was an amazing experience, and I feel that I made something that was significant in peoples’ lives, and that ultimately that’s what’s most important to me.

I say that because when I look at the film now, I’m still kind of blown away by it… with Delivered Vacant, I learned how to be a filmmaker.

**********************************************

The Hoboken Fire Victims Memorial Project has been established to honor Hoboken residents who suffered and died as a result of the Hoboken fires in the 1970s and ’80s. This past December, the Hoboken City Council voted unanimously to install a plaque honoring the 55 residents who perished in those fires. Meanwhile, another 8,000 residents were displaced by the series of suspicious fires that ultimately changed the Hoboken socioeconomic landscape forever.

***

Previous Article

Previous Article Next Article

Next Article THE FIFTH COMMANDMENT: Fleeing Nazi Persecution, Manfred Gans Fought His Way Back to Liberate His Own Family

THE FIFTH COMMANDMENT: Fleeing Nazi Persecution, Manfred Gans Fought His Way Back to Liberate His Own Family  TECHOBOKEN: Jet.com and Marc Lore Invest in the Future of Hoboken’s ‘Silicon Square’

TECHOBOKEN: Jet.com and Marc Lore Invest in the Future of Hoboken’s ‘Silicon Square’  FLUSHING PUPIE: Wading Through New Jersey’s Political Sewer, With The Plunger In Our Hands | EDITORIAL

FLUSHING PUPIE: Wading Through New Jersey’s Political Sewer, With The Plunger In Our Hands | EDITORIAL  CARRY ON: Your Hoboken Plastic Bag Ban Survival Guide

CARRY ON: Your Hoboken Plastic Bag Ban Survival Guide  BILL’S SPACE SHOW: Bad Pitches

BILL’S SPACE SHOW: Bad Pitches  BILL’S SPACE SHOW: Episode Two — Overlake, the Space Boys and Host William James Hamilton

BILL’S SPACE SHOW: Episode Two — Overlake, the Space Boys and Host William James Hamilton  WHACKED: Infamous Hoboken Mafia Hangout Faces Wrecking Ball

WHACKED: Infamous Hoboken Mafia Hangout Faces Wrecking Ball  That’s Enough Outta Me…

That’s Enough Outta Me…