HOLLY METZ & HOBOKEN’S HIDDEN HISTORY: In her new book, the author uncovers the story of Peter Lee, enslaved by the Stevens Family

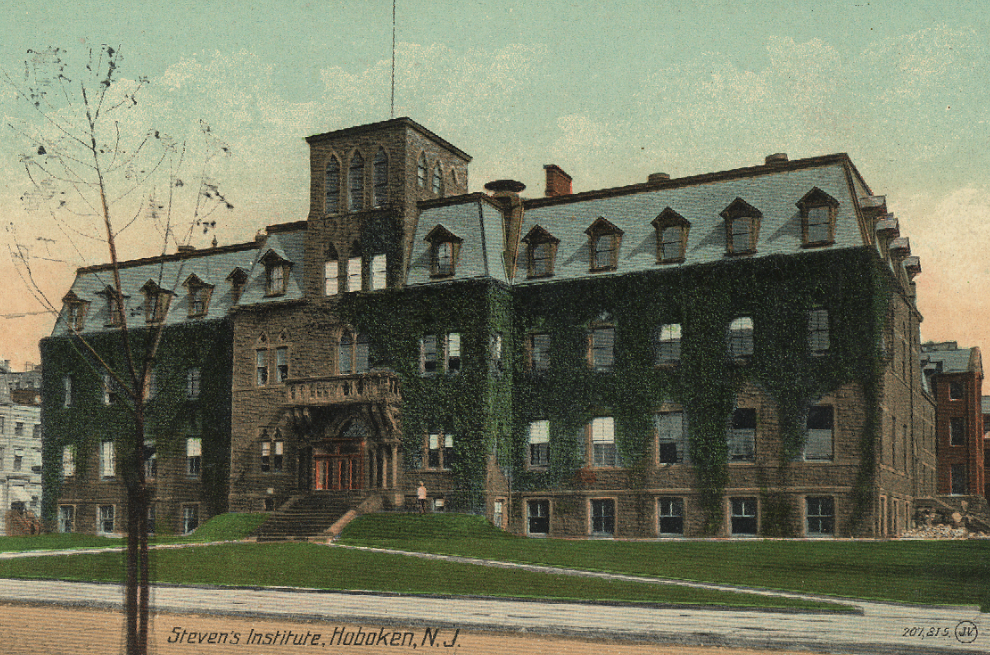

(ABOVE: photo by Robert Foster)

by Jack Silbert

As an award-winning journalist, Holly Metz has explored everything from the military testing weapons on animals, to parents’ psychiatric commitment of rebellious teens, to underground art in the former Soviet Union. But in her decades living in Hoboken, she’s also become fascinated with our town’s history. (She’s even married to Bob Foster, director of the Hoboken Historical Museum!) Metz’s latest book, The Untold Life of Peter Lee, examines the Stevens family servant whose life spanned almost the entirety of the 19th century. And her work on the topic began at the corner of 6th and Willow.

Jack Silbert: How did you first become interested in Peter Lee?

Holly Metz: Years ago I came across the only public reference to slavery in our city, a plaque installed in the Church of the Holy Innocents by members of Hoboken’s “founding family,” the Stevens Family. The plaque was presented as a memorial to Peter Lee, who had been enslaved by the Stevenses and had continued to work for them after his emancipation. But it didn’t refer to anything about his life story except his position as a slave, not even the kind of work he did.

Most of the plaque was taken up with descriptions of the accomplishments of various Stevens patriarchs. But who was Peter Lee? I decided to find out.

JS: What was your process for researching this book?

HM: Documenting Peter Lee’s life proved to be far more difficult than I could ever have imagined. In some respects his life is yet untold; some documents simply don’t exist or are wildly contradictory. The book follows my search, seeking to answer questions about Lee and his ancestors, including whether he was meant to be free from birth, but was denied his liberty by one of the Stevens elders. (Yes, is my position, based on a page from a Stevens family bible, among other records.)

I researched newspapers and censuses; reviewed military documents, plat books [which show divisions of land], and property records; and investigated original letters and ledgers at depositories. The lives of the Stevenses are recorded there in exquisite detail, but there are very few references to the lives of the persons they enslaved. One exception to this is the ledgers kept by Stevens patriarch John II, and the letters he exchanged with his brother-in-law, which detail their lucrative trade in enslaved Africans. This has never been publicly acknowledged.

JS: Many of us have misconceptions about the north and south in regards to slavery. What can we learn from the individual story of Peter Lee that gives us a more complete picture of slavery and the north?

HM: Slavery was practiced in every one of the 13 colonies. In the north, New York had the highest number of enslaved people; New Jersey was second. By tracing the life of Peter Lee and the lives of his ancestors, readers can better understand the depth of northern slavery and the vicious New Jersey laws that upheld and enforced it.

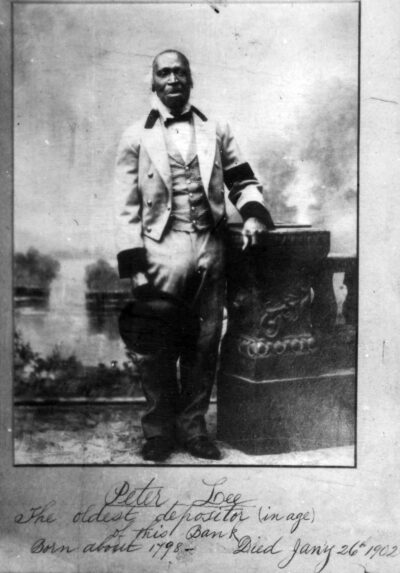

image courtesy of the Hoboken Historical Museum

JS: Where did you grow up and what sparked your interest in history?

HM: I was born in Brooklyn but my family moved to the sandy, south shore of Long Island (near Jones Beach) when I was young. It may be that moving to a Levitt house in the 1960s, to a new development that bore no traces of any past, began my curiosity about what had gone before. But my understanding of the complexity of the past, and our relationship to it, probably began in earnest when my dad, a high school teacher, was awarded a sabbatical, and we moved to London. I had just completed sixth grade. Suddenly I was immersed in another culture, with very different stories about the past from those I’d heard in my suburban American classrooms, including stories about empire and the role of the Church (Church of England) in our school. My public school in the U.S. had not had morning prayers and we certainly didn’t assert an allegiance to the Queen.

JS: How did you start in the writing field?

HM: I began as a journalist during the period just before a journalism degree was mandatory to find work—though since I worked as a freelancer, editors seemed most concerned with the quality of my clips. Working freelance allowed me to pitch articles about topics that interested me—mostly social issues, but also stories about the arts, and sometimes when those two intersected.

JS: What first brought you to Hoboken?

HM: I checked out Hoboken when I graduated from college. I’d heard it was close to New York City, where I’d be most likely to find work. The PATH was then 30 cents, and I’d heard I might find an apartment I could afford on a safe street. What I wasn’t prepared for was how I’d fall in love with the city right away, with the way light fell on the painted facades, the human scale of the buildings, the openness of so many of the people I met. Hoboken seemed like an Edward Hopper painting come to life. When I saw the housedress-wearing ladies on Washington Street, so comfortable they were wearing their fuzzy slippers on the main street of town, I knew I had to live here.

Peter Lee photo retrieved from the Rutgers University Community Repository; photo negative held at the Hoboken Public Library

JS: In 2000, you founded the Hoboken Oral History Project. What was your motivation and why do you feel it’s so important?

HM: The Hoboken Oral History Project is meant to record the life stories of working-class people in this city—the people who made their living on the working waterfront, or in manufacturing plants like Maxwell House and Tootsie Roll, or in Mom and Pop shops, or taverns, or in garment factories—an everyday history that spans many generations, but which has not been well acknowledged in books and newspapers (unless tied to disasters), and which has been disappearing as the city and its population have gentrified and changed. I wanted to record how people, mostly of modest means, have lived in this place. We gather stories and print them into booklets that we distribute for free at the Hoboken Historical Museum, and we encourage people to tell even more even more stories at the release events. Old-timers and newcomers meet, all in appreciation of our city’s history and way of life, and the people who have sustained it for so many years.

JS: Your body of work might paint you as a very serious, academic person. Can you reveal the lighter side of Holly Metz?

HM:It’s true, my work tackles heavy subjects. But I really like to laugh and be silly, and am drawn to people who do, too. That’s what’s kept me balanced, and on track, through years of difficult research. And of course there’s always chocolate.

JS: Your previous book, Killing the Poormaster, resonated with modern readers because of its explorations of City Hall corruption, union busting, and society in the wake of economic collapse. What do you hope that readers of The Untold Life of Peter Lee will be able to apply to current issues?

HM: I hope readers of The Untold Life of Peter Lee will begin to reflect upon (and read more about) northern slavery and consider how we are carrying this largely unrecognized history, how it weighs upon us today. It’s the legacy of all Americans and we have to start talking about it. Slowly we are beginning to see its long reach—made plain in studies like Craig Wilder’s Ebony and Ivy on the ties between Ivy League colleges and slave traders, and in conversations that are coming up about a reparations bill.

JS: In your time in Hoboken, what has changed for the worst, and what has changed for the best?

HM: Hoboken is no longer the human-scaled city I first encountered. I feel that loss. New buildings boast a lot of height and glass and reflective surfaces. The city often feels less welcoming and warm, but then I’ll go to a release event at the Hoboken Historical Museum of one of our oral history booklets and I will find old-timers and newcomers together, sharing stories, kibitzing. There have always been places for Hobokenites to meet, and this is a relatively new one (since 2001), dedicated to the city and its people. I’m glad we have it, and hope people realize it is an independent cultural institution, sustained by supporters, and keep it going through donations or volunteering.

———————-

The Untold Life of Peter Lee by Holly Metz is available from the Hoboken Historical Museum (1301 Hudson St.) and also at Little City Books (100 Bloomfield St.).

Previous Article

Previous Article Next Article

Next Article THIRD WARD: Ron Bautista / Michael Russo | Hoboken City Council Candidate Questionnaire — VOTE NOV. 5, 2019

THIRD WARD: Ron Bautista / Michael Russo | Hoboken City Council Candidate Questionnaire — VOTE NOV. 5, 2019  THE MILE SQUARE ADVANTAGE: Drummond St. Strategy Founder James Runkle Defines the Value-Add of Hoboken

THE MILE SQUARE ADVANTAGE: Drummond St. Strategy Founder James Runkle Defines the Value-Add of Hoboken  ASK YOUR BARTENDER: Madison Bar & Grill’s Allison Friedman

ASK YOUR BARTENDER: Madison Bar & Grill’s Allison Friedman  ALESSI’S MORE: Vocal Powerhouse Christina Alessi Releases a Brand New EP

ALESSI’S MORE: Vocal Powerhouse Christina Alessi Releases a Brand New EP  Hoboken Artist Maggie Hinders on Display at SOMA Studio Tour — June 2nd & 3rd

Hoboken Artist Maggie Hinders on Display at SOMA Studio Tour — June 2nd & 3rd  FACES: James Myers — Comedian, Winner of the Hoboken Comedy Festival

FACES: James Myers — Comedian, Winner of the Hoboken Comedy Festival  FACES: Meredith Ochs — Radio Personality

FACES: Meredith Ochs — Radio Personality  Former Hoboken Resident Retiring From Job

Former Hoboken Resident Retiring From Job