Picturing Hoboken: A Haven for Artists

Story by Melissa Abernathy

Images courtesy of the Hoboken Historical Museum

On an 1881 map in the Hoboken Historical Museum’s recent exhibition, “Mapping the Territory,” was an intriguing notation. The words “Artists Retreat” were emblazoned across a strip of land owned by the Hoboken Land & Improvement Company between Hoboken and Weehawken, begging the question: Was this some clever marketing ploy devised by the Stevens family’s real estate enterprise to enhance the area’s appeal? Or was Hoboken really once a haven for artists?

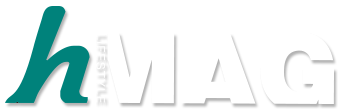

Before the transatlantic shipping lines arrived in the late 1800s, fueling an industrial and population boom, Hoboken was indeed known as a bucolic getaway for New Yorkers. Scores of artists painted scenes of the “countryside” just across the river for magazines and for fine art collectors, including Hudson River School painters, Asher Brown Durand (1796-1886), born in Maplewood, N.J., and William Rickarby Miller (1818- 1893), who immigrated from England.

Drawn by the natural beauty of the Palisades cliffs, and the views Hoboken offered of New York Harbor, these artists painted scenes that are virtually unrecognizable to us today: pastoral landscapes, a harbor filled with sailboats, shady pathways, and 19th century gentlemen and -women at leisure. Durand is best known for the iconic Hudson School painting “Kindred Spirits” (1849), of the painter Thomas Cole and the poet William Cullen Bryant meeting in the Catskills, which was reportedly bought for $35 million by Walmart heiress Alice Walton for the Crystal Bridges Museum in 2005.By the late 1800s, Hoboken had become a major port, attracting a new school of painters, the Hoboken School of Marine Painters, led by Antonio Nicolo Gasparo Jacobsen (1850-1921). In 1873, Jacobsen arrived in New York from Denmark as an accomplished musician who briefly found work as a violinist, but his skill at sketching boats on the harbor attracted commissions and he soon evolved into one of the most prolific – and enterprising – painters specializing in portraits of boats.

Jacobsen’s work today fetches hundreds of thousands of dollars at auction, but he sold his paintings to boat owners, captains and crew members for a mere $5 to $15, depending on the canvas size. Over a 40-year career, he turned out an average of 4 – 5 paintings per week, earning enough to build a comfortable house on the Palisades and entertain friends who shared his passion for music. The artist’s father was a violin maker and his first three names derive from the three best-known violin makers of Europe.

Jacobsen cleverly added his address to his signature on his paintings, ensuring that anyone admiring his work could locate him for a commission of their own at 705 Palisade Avenue, West Hoboken (now part of Union City). The Museum curated an exhibit in 2003 featuring Jacobsen’s vivid scenes of schooners, yachts and other ships at sea, usually painted in profile, sometimes in dramatic, stormy weather, other times clipping briskly along on sunny waters.

A contemporary of Jacobsen’s, Charles Schreyvogel (1861 – 1912), painted in a completely different style, specializing in Western subjects, just as the frontier was beginning to disappear. Born into a poor German family on New York City’s Lower East Side, he spent part of his childhood in Hoboken, and established his studio there. Schreyvogel was captivated as a young man in the 1880s by “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show,” but as he couldn’t afford the trip out West until 1893, he used models and props to stage his own Western scenes on the rooftop of his Hoboken apartment building. Despite the artificial setting, he developed into one of the most admired of the Western painters, whose work was championed by Theodore Roosevelt and is featured today in many prominent museum collections.

The Wild West’s connection with Hoboken is not as far-fetched as it may seem; P.T. Barnum is credited with popularizing Western spectacular shows with his “Grand Buffalo Hunt” first staged on Hoboken’s Elysian Fields in 1843. Schreyvogel’s career was cut short at 51, when he died of blood poisoning in Hoboken, and he is buried in Flower Hill Cemetery in North Bergen.Two of Hoboken’s most famous native-born artists are the world-famous photographers Alfred Stieglitz (1864- 1946) and Dorothea Lange (1895-1965), who were born into Hoboken’s highly educated and culturally oriented German immigrant community in the latter part of the 19th century.

Born in 1864, the eldest of six children in a prosperous immigrant family from Germany, Stieglitz later proudly declared: “I was born in Hoboken. I am an American. Photography is my passion. The search for truth my obsession.” The family lived at 500 Hudson Street, which bears a historic plaque marking his birthplace, until he was 7, when they moved into New York City. Alfred’s father was a wool merchant and an amateur painter, and the Stieglitz home was often filled with artists and musicians.

While studying in Germany in the 1880s, Stieglitz discovered the new medium of photography and soon became the most visible and acclaimed artist in the medium, earning more than 150 awards by 1902. He opened a gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue in 1905, later known just as “291,” which fostered the careers of some of America’s best-known cutting-edge artists and photographers. It was there he met the young artist Georgia O’Keeffe in 1916, and by 1918, had left his wife to move in with her. Despite a 23-year age difference, the two married in 1924. His gallery became a center of the international avant-garde art movement.Three decades later, Dorothea Lange was born into a second-generation German-American family in 1895, at 1041 Bloomfield St. in Hoboken. Though less affluent than the Stieglitz clan, her family shared the strong belief in education and the arts. She was born Dorothea Margaretta Nutzhorn, but after her father abandoned the family when she was 12, her mother found work on the Lower East Side, and Dorothea finished her schooling in New York City. She enrolled in teachers college, but dropped out to apprentice at the professional studios of Arnold Genthe and Clarence White.

Two other artists closely associated with Hoboken came as students at Stevens Institute of Technology: John Marin (1870-1953) and Alexander Calder (1898–1976).

Marin, considered one of the most innovative artists of the early 20th century American avant-garde, was born in nearby Rutherford, NJ, and raised in Weehawken. He aspired to become an architect when he enrolled at Stevens in 1886, but he dropped out to work as a draftsman in an architectural firm. After a few years in the field, he switched course in 1899 and enrolled in art school, first in Philadelphia, then the New York Art Students League in 1902. On a trip to Paris in 1909, he met Alfred Stieglitz, who became Marin’s great champion, and they were part of the New York City avant-garde movement.

Calder, from a family of prominent Philadelphia artists, enrolled at Stevens in 1915 to study mechanical engineering, and his dorm room was in the tower of the former Stevens Castle! His engineering studies enabled him to excel in the art of constructing the mobiles and stabiles that he is best known for today. The shapes in Calder’s work echo the enormous ship propellers that were once made by Ferguson Propeller Works (1128 – 32 Clinton St.). Calder also worked as a hydraulic engineer and traveled the world by ship, settling for a while in Paris, where he befriended the avant-garde artists gathered there: Mondrian, Picasso, Miró and Le Corbusier.

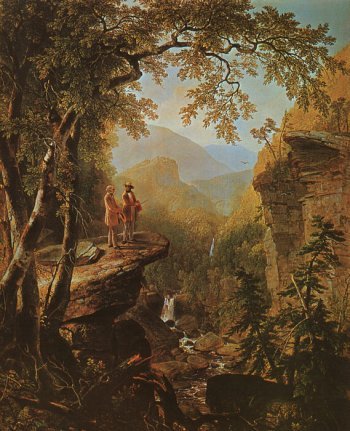

Traveling in the opposite direction, the great 20th century abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning (1904–1997) arrived in Hoboken from the Netherlands in 1926 as a penniless stowaway on a European freighter, knowing very little English. He found lodging in the Holland Seaman’s Home at 332 River St., and worked for a year as a housepainter in Hoboken, which gave him an income and time to learn English. He soon abandoned Hoboken for the New York City art scene, and developed into one of the most acclaimed and collected painters and sculptors of the 20th century.Other New York artists sought out Hoboken for the gritty, bustling urban setting, including Stuart Davis (1892- 1964) and several of his fellow artists from Robert Henri’s School of Art in New York City, center of the Ashcan School of urban realist painters. Davis produced a book called “The Hoboken Series,” from a 1978 show.

In the 1970s and 80s, Hoboken was the Greenpoint of its day—attracting artists and musicians with affordable rents and a safer vibe than most comparable neighborhoods in New York. Most importantly, the abundance of abandoned factory buildings provided large and light-filled studio space.

Some of these factories-turned-studios can still be seen today on the annual November Artists Studio Tour. They include the former Levolor Blinds factory at 720 Monroe St., the Neumann Leathers factory on Observer Highway, and the My-T-Fine Pudding Factory at Harrison and Newark Streets. Tragically, one former factory, at 720 Grand St., was discovered later to have too much residue from its former occupant, a mercury vapor lamp manufacturer, and the artists who were converting it to live-work space were evacuated and the property razed and treated as a Superfund site.

And, of course, the Hoboken Historical Museum, at 1301 Hudson St., a former Bethlehem Steel ship repair facility, hosts six art exhibits a year in its Upper Gallery space. It’s open 6 days a week, for a small donation of $3 per visit. Annual membership is a great way to keep a cultural institution alive, just $50 for individuals and $75 per family.

Before the transatlantic shipping lines arrived in the late 1800s, fueling an industrial and population boom, Hoboken was indeed known as a bucolic getaway for New Yorkers. Scores of artists painted scenes of the “countryside” just across the river for magazines and for fine art collectors, including Hudson River School painters.

Previous Article

Previous Article Next Article

Next Article FRIDAYS ARE FOR FRANK: “Swinging On A Star” | Sinatra Memorial Returns to 415 Monroe Street

FRIDAYS ARE FOR FRANK: “Swinging On A Star” | Sinatra Memorial Returns to 415 Monroe Street  READ ALL ABOUT IT: The Hoboken Public Library Celebrates 125 Years of Greatness and Community Leadership

READ ALL ABOUT IT: The Hoboken Public Library Celebrates 125 Years of Greatness and Community Leadership  FRIDAYS ARE FOR FRANK: “You Might Have Belonged To Another” (w/ The Tommy Dorsey Orchestra)

FRIDAYS ARE FOR FRANK: “You Might Have Belonged To Another” (w/ The Tommy Dorsey Orchestra)  THIS TOWN: Sinatra Biographer James Kaplan Discusses Frank’s Relationship with Hoboken

THIS TOWN: Sinatra Biographer James Kaplan Discusses Frank’s Relationship with Hoboken  GRANDEVOUS: Leo’s Celebrates 80 Years of Serving Hoboken

GRANDEVOUS: Leo’s Celebrates 80 Years of Serving Hoboken  FRIDAYS ARE FOR FRANK: “Wives and Lovers” (feat. Count Basie)

FRIDAYS ARE FOR FRANK: “Wives and Lovers” (feat. Count Basie)  FRIDAYS ARE FOR FRANK: “Time After Time”

FRIDAYS ARE FOR FRANK: “Time After Time”  REMEMBERING THE FIRES: All Saints Church to Commemorate Those Lost in Series of Hoboken Fires

REMEMBERING THE FIRES: All Saints Church to Commemorate Those Lost in Series of Hoboken Fires

testing omment