WHY SINATRA STILL MATTERS — A Frank Discussion with Author Pete Hamill

by Christopher M. Halleron

photos by Craig Wallace Dale

Over the years, Frank Sinatra had his issues with the press. One night in 1947, he spotted newspaper columnist Lee Mortimer in Ciro’s Restaurant on LA’s Sunset Strip and cracked him in the mouth. With all the nasty things Mortimer had to say about Sinatra, most people agree he had it coming.

But then there were guys like Pete Hamill. Having made a name for himself as an honest and urbane writer at The New York Post and as a correspondent for The Saturday Evening Post, through the course of a number of fortuitous events Hamill eventually found himself in the company of Sinatra on a regular basis.

“I never asked him, ‘why are you friendly with me,‘ because that’d be ridiculous,” says Hamill, sitting over plate of Veal Parmagiana at Leo’s Grandevous, a renowned family-style Italian restaurant in the back end of Hoboken.

The legend that is Frank Sinatra will turn 100 this year—born on December 12, 1915 just a few blocks away from Leo’s at 415 Monroe Street in Hoboken. Of course the man, Frank Sinatra, passed away in 1998. Soon after his passing, Pete Hamill wrote Why Sinatra Matters—a book with a title as straightforward as the man who wrote it, exploring the complicated life of a man who was so much more than just some singer.

The legend that is Frank Sinatra will turn 100 this year—born on December 12, 1915 just a few blocks away from Leo’s at 415 Monroe Street in Hoboken. Of course the man, Frank Sinatra, passed away in 1998. Soon after his passing, Pete Hamill wrote Why Sinatra Matters—a book with a title as straightforward as the man who wrote it, exploring the complicated life of a man who was so much more than just some singer.

“I thought the things that the obits said about him didn’t do him justice. They didn’t talk about the things that really mattered about Sinatra,” says Hamill. “It wasn’t about the women—it was much more important.”

Ours was certainly not the first conversation about Frank Sinatra in Leo’s. The place is essentially a shrine to Hoboken’s famous son, with Frank’s image looming large on every square inch of wall space. With “Strangers in the Night” doobie-doobie-doing its thing on the jukebox, Hamill explains, “What I was trying to do with the book was explain that there were six or seven girlfriends—and they were all consenting adults. But the only two women in his life that affected his music were Nancy [Barbato-Sinatra], and Ava Gardner.”

Sinatra notoriously left his first wife Nancy for Ava—a move that left him reeling for years and years to come. “You know Ava, she knocked him on his ass, with a lot of help from him himself. But he got up,” says Hamill, “and I’m pretty sure that this had something to do with Hoboken, and the Hoboken nature. Because it was certainly true in Brooklyn where I grew up—if you were knocked on your ass, you had to get up. These were people who got up.”

Skinny Kid From Hoboken

Hamill’s Why Sinatra Matters is both personal and intuitive, as much a biography of Sinatra as it is a memoir of his impact on Hamill over the years—even prior to their introduction. Published in the wake of Sinatra’s death by Little, Brown & Co., the book was instantly hailed as one of the most insightful accounts of Sinatra the man, as opposed to Sinatra the legend. In fact, Sinatra had once asked Hamill to co-write his autobiography, but it never came to be. Why Sinatra Matters was a product of those in-depth personal conversations and shared experiences. “Tina [Sinatra] let me know that my book was the best she had ever read about her father,” says Hamill. “She has a sense of irony, and she remembers certain things from Frank.”

The legend of Frank Sinatra is that of a jet-setting playboy, but the man was significantly more family-oriented than the tabloids of the day would ever let on.

Hamill credits his family life in Hoboken with Sinatra’s tenacity. “Just talking to him here and there, I got a sense that it was built in. I’m not sure whether that was from his father, but it was most likely from his Mother, Dolly.”

Dolly Sinatra moved from Italy to America at a very young age. She married Marty Sinatra, and became quite the local political force. In 1919 she chained herself to Hoboken City Hall. Soon after that, she became head of the local Democratic ward. The Irish, who ran Hoboken at the time, used Dolly’s influence to secure the Italian votes. Eventually the Sinatra family opened a tavern called Marty O’Brien’s on the corner of 4th & Jefferson.

“I remember he told me, ‘My mother kept a bat behind the bar, and she’d go WHACK, and then hug me… and I married the same woman every time,’” recalls Hamill.

“One of the regrets I had about not doing the book (Sinatra’s autobiography)—he didn’t talk much about the father, although the father did very well in the Fire Department. It’s in the verbal history of Hoboken that he did well.”

Hamill credits Sinatra for contributing significantly to an overall Italian-American ascendancy in this country. “The combination of Sinatra, DiMaggio and LaGuardia—who were more or less simultaneous—changed the image of the ‘illiterate sons of Italy.’ It gave people like me—the Irish; we didn’t know what the hell to think about most things—and it gave us a way to think about emotion, having an emotional life.”

Sinatra evolved from the relatively rough streets of Hoboken to become a romantic idol. But in the process, he changed the outward perception of the rugged American male. “It was different, with Sinatra saying you can have emotion,” says Hamill. “You can have your heart broken and walk away, it’ll be ok, the sun will come up. It’s quarter to three, there’s no on in the place except you and me,” he says. “It was the blues, without self-pity.”

Craftsman

Of course any conversation about Sinatra is superficial without discussing his overwhelming talent as a performer.

“I did ask him once if he saw himself as a singer or a musician, and he thought very much so, a musician—‘My instrument is the microphone,’” says Hamill of Sinatra.

“Sinatra learned a lot about breathing from Tommy Dorsey, which was how he could hold a note so long. He saw [Dorsey] playing trombone and notice he was sucking air in on the side of his mouth, so Sinatra learned how to do that with his voice. He could talk as a good craftsman. You can’t become an artist unless you first master the craft,” says Hamill. “Craft is important. So at the Rustic Cabin he learned how to do certain things and ended up exploding at the Paramount.”

Sinatra’s performances at the Paramount more or less cemented his stardom, but over the years that cement would erode away time and again. What he had in his corner, spurring him on to continually fight his way back into the spotlight, was his iconic individualism.

“’I don’t want to SOUND LIKE Bing Crosby, I want to be as BIG as him,’” says Hamill of the mindset behind Sinatra’s authenticity. “Most of the writers I know and most of the performers I met here or there—they were not competitors, the didn’t say they wanted to ‘be better than Bing Crosby,’ they said, ‘I want to be the best version of Pete Hamill that ever lived.’ Not the best column writer, the best me—and then I can trust it. I can trust that I’m not living off some other guy’s plate, you know, and go to bed at night.”

Frank v. Hoboken

On the topic of authenticity, it should be noted that Sinatra and Hoboken didn’t always get along. Frank was once pelted with tomatoes while performing here in town, and it created a mythical disdain for his birthplace—all of which fell to the wayside in later years.

On Sinatra’s relationship with Hoboken, Hamill says, “It reminded me of a line from [William] Faulkner, who said he ‘loved Mississippi—in spite of, not because.’”

With the Mile Square City relishing the attention from Frank-o-philes celebrating his centennial, one might wonder what Sinatra would think of it all.

“Whether he admitted it or not, I think he’d be delighted,” says Hamill.

“In the end, with all the things that were said about him, the people who hated him, he added to the world—he didn’t subtract from it. He didn’t live a performance; he lived a life and accomplished something in that life, changing the soundtrack of a couple generations.

“It wasn’t simply WWII, it was the post-war, it was the 60s; it was the thing that existed from the past, in spite of rock and roll. I think he didn’t need to apologize for the art. He wasn’t cruel; he wasn’t cynical.

“He learned, I think from Billie Holiday, how to take a song and make it art—written by other people and make it autobiography. Not an easy thing to do, whether it’s Rigoletto or Rodgers & Hart. I would bet if he lived to be 100—and in certain ways he did; his work is alive—but if he had lived to 100,” says Hamill, “I think he would have smiled.”

“He outlived Lee Mortimer.”

Previous Article

Previous Article Next Article

Next Article UGLY, EVEN FOR HOBOKEN: Six Months Since Forged Xenophobic Fliers Put Mile Square Politics Under Worldwide Scrutiny

UGLY, EVEN FOR HOBOKEN: Six Months Since Forged Xenophobic Fliers Put Mile Square Politics Under Worldwide Scrutiny  The Beat Goes On — Examining the Current State of the Hoboken Live Music Scene

The Beat Goes On — Examining the Current State of the Hoboken Live Music Scene  REGISTER TO VOTE: 2019 — Deadline Tuesday, October 15; Local Elections Are Where Your Vote Counts Most

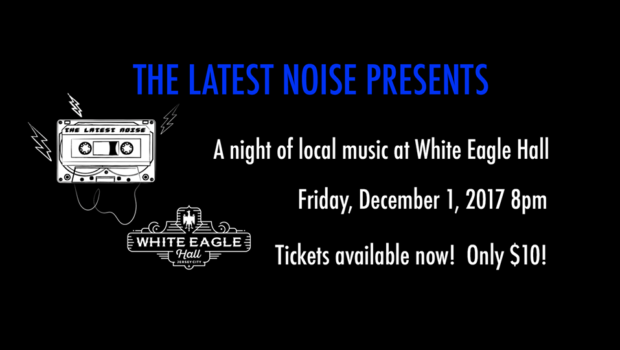

REGISTER TO VOTE: 2019 — Deadline Tuesday, October 15; Local Elections Are Where Your Vote Counts Most  CATCH ‘EM WHILE YOU CAN: Area Talent Flocks to White Eagle Hall — FRIDAY, DECEMBER 1st

CATCH ‘EM WHILE YOU CAN: Area Talent Flocks to White Eagle Hall — FRIDAY, DECEMBER 1st  BILL’S SPACE SHOW: Bad Pitches

BILL’S SPACE SHOW: Bad Pitches  ADAM WADE: ‘LIVE AT THE MAGNET THEATER’ — Hoboken Humorist/Superstar Storyteller Releases His Second Album

ADAM WADE: ‘LIVE AT THE MAGNET THEATER’ — Hoboken Humorist/Superstar Storyteller Releases His Second Album  BRIDGE OVER TROUBLED WATER MAINS: Hoboken and SUEZ Announce Formation of Public Water Utility, New Service Contract

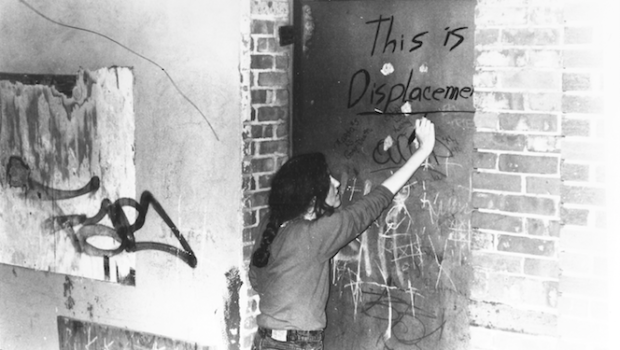

BRIDGE OVER TROUBLED WATER MAINS: Hoboken and SUEZ Announce Formation of Public Water Utility, New Service Contract  EXCLUSIVE: Filmmaker Nora Jacobson Discusses ‘Delivered Vacant’, the Award-Winning Documentary on Gentrification in Hoboken

EXCLUSIVE: Filmmaker Nora Jacobson Discusses ‘Delivered Vacant’, the Award-Winning Documentary on Gentrification in Hoboken